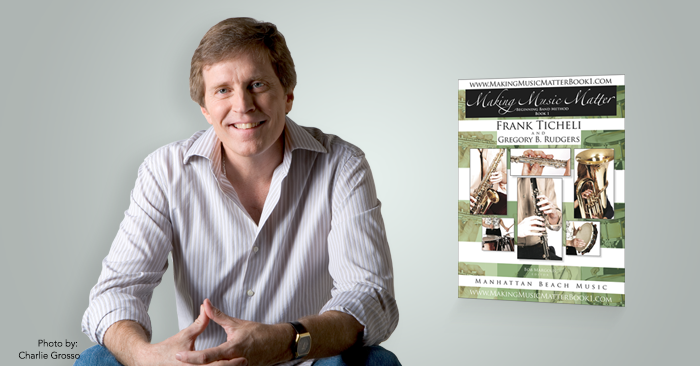

“Making Music Matter” is a new beginning band method created by Frank Ticheli and Gregory B. Rudgers and published by Manhattan Beach Music. You can flip though the pages of the teacher’s edition below:

I’m delighted to announce that “Making Music Matter” was added to SmartMusic this month. I’m equally delighted to share the following in-depth interview I recently conducted with Frank, in which he generously shared stories, advice, and discussed the creation of (and innovation in) this exciting new method.

We’re here at the SmartMusic studios and I’m joined by Frank Ticheli, and we’re going to chat about his new method book, Making Music Matter, published by Manhattan Beach Music. Frank, first of all, thank you so much for being here and sharing your insights today.

Thank you Ryan, it’s a pleasure to be here.

One of the things I noticed right away when I picked up the Teacher’s Edition was that there are introductions to each lesson, that as an educator I now have access to everything, from those pesky bassoon fingerings that I never remember from methods class, all the way to performance notes for those pieces at the end of each lesson.

I know it will be a great convenience to have that right before the lesson – boom! here’s what you need, here’s what your kids are gonna learn. And then I have my notes: here are some things you might want to talk about with the kids. So you’re able to pace it, and the most important thing is that you’re able to provide kids with an opportunity to have, on a regular basis, a sense of accomplishment. Regularly-paced rewards. Now we can do THIS, now we can play THAT piece. Then you go on to the next lesson and so forth.

I think this will help teachers pace their lessons and in a logical way present kids with challenges in ways that don’t overwhelm them. Because what I don’t like about some of the other books is, “We’re on page 18 and we don’t know why we’re on page 18. Now we’re on page 19. Why page 19? We don’t know.”

Also, Ryan, we’re introducing them to real music right away, but we’re also being realistic here. We’re introducing things a little at a time. I think this is one of the great strengths of the book, actually. We introduce only a few things at a time: they have exercises, then they have a real piece that summarizes what they’re introduced to. Then you go on to the next lesson.

None of the other books do that.

To me it seems like such an obvious way to go about introducing kids to music and I’m kind of surprised that there aren’t books out there that are divided into little chapters where you learn this in this chapter, and that in the next chapter.

I’m looking at the notes for Lesson 3. Some of the examples involve you explaining why you’re teaching flute and oboe low Eb in this lesson versus a different lesson, and that’s the kind of detail that makes this book useful for the beginning band director . Did you write any of these lesson plans with new teachers in mind or do you think this will apply to everybody?

I think it’s going to apply to everybody. We thought about writing more, but the things we threw out were the things we thought might be A.) insulting to teachers, and B.) telling them too much how to do their job. We tried to stay out of the way of that and instead offer them signals regarding where we were and what we were thinking as we were designing this lesson. So they understand what our thinking was.

So that Eb you mention, it’s interesting you mention that. We’re basically saying, “Yes, we introduce flutes to a low Eb here, pretty early on, but don’t worry about that, we’re only doing this because in the back of the book there’s an Eb major scale and the flutes need to know that and the oboes need to know that to play that. But we know that’s a tough note for young players, so guess what, we’re not going to use that for many of the next lessons because we know that that’s kind of low.” So we’re kind of reassuring them – we’re letting them in on our thinking.

I think that’s a huge help to educators of all experience levels. I know as a brass player myself every tidbit I could get about flute in 5th and 6th grade is super helpful, and that’s certainly why I noticed that one right away.

Well then you would like that there are little special notes that we interspersed all through the lesson. Like “Clarinet Reminder” – little things like remind the clarinets to keep their corners tight and make sure the holes are covered well and if they’re squeaking it might be because air is leaking. Little things like that – that we brass players need to be reminded of – I think are very useful. And it’s good for the kids to get those reminders.

The book is comprehensive then from start to finish. It’s not just set up so the kids are working in steps, it’s also easy for the instructors to operate by steps. What other things similar to those lesson plans at the beginning of each lesson do you think are in the book that could be especially helpful on that day-to-day basis?

There are a lot of things. First of all, the book is interspersed with wonderful warm-up exercises that Greg Rudgers designed. It’s not just exercises and then play the Ticheli composition, now another set of exercises then play another Ticheli composition. To us even that could become monotonous, so we break it up with warm-up exercises and also I’ve interspersed something called Creative Corner.

These are little elementary composition exercises for the kids. It will help teachers to expose kids to creative thinking, to the actual creation of music. In other words, composition in ways that are not intimidating, because these composition exercises don’t require you to understand that you shouldn’t double that leading tone and maybe that parallel interval isn’t the best interval – you don’t get all this theory that can be intimidating to young kids. Instead it’s just celebrating creativity with sound in ways that I think the kids will enjoy, and it might excite them down the road in the future to consider composition as something they might like to do themselves. So that’s there.

Then in the back of the book there are solo pieces for every single instrument – either solo unaccompanied or solo with piano – for each of the instruments. think of those as kind of a rewards for the kids because they will have reached the technical ability to play those solos when they are nearing completion of the book.

I’d love to know more about the Creative Corner. Is this something that involves more improvisation or something that looks more like a theory exercise, or how are those lessons structured?

I actually give them something that Mozart used to give his students. He would start a phrase and he would say, “Here, would you please finish this for me.” I thought if it was good enough for Mozart, it’s good enough for us. (Laughs).

So I give them this little fragment: (Sings) ‘mi-mi-fa-sol-fa-mi-mi.” Then in the next few bars I leave it blank and the students fill it in. I give them a rhythm suggestion: (Demonstrates) “half-quarter-quarter quarter-quarter-half” and they come up with the pitches, so it’s very simple. I’m giving them structure, I’m giving them rhythms even – they just have to add pitches. And when you say improvisation, I recommend they start out on their instruments to improvise different possibilities, then pick one and write it down.

Whereas if you skip to Creative Corner # 3, that one celebrates possibility and even wildness. There are no pitches, no rhythms, it’s just a little box where students get to make sounds just with their body. I break them into groups and they make all these wonderful sounds with their mouth, with their bodies, with their hands. Any kind of sound they can make with the human body and turn that into a piece.

So that takes away not only theory, but takes away traditional notation, and you just sort of enter this world of “What if?” You get to ask the question, “What if?” and you’re just dealing with a world of sound and time and how sound interacts in time. So I think that will be a really fun one for the students.

I’m trying to make composition fun and to remind students that actually the most important thing for a composer is not learning theory, but in having an open mind, having the courage to try things, and to take chances. And that’s sort of what these exercises celebrate.

So in some spots it sounds like they’re synched up in terms of solfège and rhythmic duration with the things that the students are learning in the lesson, but at the same time they’re giving students a huge amount of freedom to make sure that students develop their musical ear – in other words to make the music matter.

That’s right. Sometimes they’re related to their instruments; sometimes they’re completely separate from what they’re learning on their instruments and it’s reminding them that “Oh music can be this too! I didn’t know it could be that.” You mentioned solfège. I sang it in solfège but it’s not in solfège in the book, it’s just pitched.

You also mentioned the solo rep at the end of the book and said it’s kind of a reward for students that are getting ready to finish up the method.

That’s right.

Is that something you would encourage teachers to use in class or is that something really to be used as a reward, for the students to work on in their own personal time?

I think there are a lot of ways they could be used. Yes, teachers could be involved in this. The students could just use these to practice at home just for fun. The students could play them for family or friends separately from school. Or teachers could put them on as part of their evening concert.

They could showcase some of their students at intermission, before the concert, or even as a regular part of the concert. You have a parent play the piano and you bring out your student clarinetist or a student oboist or a student trombonist and you have them play a piece one after another, and then you get back to the full band. So it could even be incorporated into a regular band concert.

They could be used in private lessons with private teachers. I suppose students could use them to play in solo and ensemble contest – some states have them even at this young level. There’s unlimited possibilities for how those solo pieces could be used.

One of the other things I noticed in the book was a percussion ensemble piece. I know that –again as a brass player – that’s a little intimidating. I’ve never conducted a percussion ensemble – I’m nervous enough getting some patterns on the bells going.

(Laughs)

How accessible is it, how do you recommend teachers work with it, is it for the middle of the year, end of the year?

Yeah, you have to remember that this is a really straightforward simple percussion ensemble piece. It’s meant for kids that are probably finishing their first year, so it’s pretty simple. The percussion score fits on left and right facing pages; there are no page turns for the conductor even. The parts are very simple, very straightforward.

I can’t imagine anyone, even a young music educator, having any trouble with this little percussion ensemble piece. I could have included a solo xylophone and piano piece, but I wanted to include something different for the percussion, where they have this chance to do something, make a whole piece together without the rest of the band there.

So often for percussion when they’re playing with the band they’re in the back back there, they are supporting the band – the woodwinds have the melody and the harmony is in the brass and woodwinds, and the percussion are often relegated to having a supporting role. I wanted to give them something where they get to have the spotlight as a section, and that’s the reason for the piece I wrote called “Steamroller.”

And also lots of schools have percussion coaches, so if there are teachers intimidated by the percussion – I can’t imagine too many would be intimidated by this little piece – they could certainly rely on their percussion coach if they have one. If not, sorry you’re out of luck! (Laughs).

So no funky timpani tunings or advanced stuff going on, this is pretty straightforward. Like the solos, it’s designed to get the students at the end of their first year doing something fun and unique that shows off their work.

That’s right. When we get to Making Music Matter Book 2 I did actually include both – a xylophone and piano solo and another percussion ensemble piece. So they actually have 2 choices when you get to Book 2, the percussionists.

Speaking of some odd instruments, do these compositions that are at the end of every lesson work with reduced ensembles? I know I’ve certainly taught at schools where we didn’t have bassoons in 6th grade for all sorts of reasons. Is that the kind of thing the compositions can work around?

Yes, they’re going to work very well for reduced instruments. You’ll notice the scores – this is one reason our teacher’s book can be so light and small compared to so many of them out there which are thick and heavy. The reason ours can be smaller and a little more handy is because we’ve scored them in these reduced scores where I have the flutes and oboes and bells together, I have all the low woodwinds and low brasses together on a staff.

So that enables those bands who don’t have the bassoons or maybe don’t even have tubas or enough horns, it enables them to play all of these exercises and compositions without those instruments or without sufficient quantities of those instruments. Not only that, but I even have a piano reduction provided below each composition so that if there are whole instruments missing even with this condensed score, say you’ve got no clarinets for some reason, well, you can have a pianist – a student or even the band director – can just play the clarinet part, or play along on the piano. So you have lots of flexibility in how you deal with these pieces.

What was your inspiration for creating the book? Did you see some gap in the marketplace? Did you work with some bands that were clearly struggling with technique? Was it just time to do a method book – the full band compositions had gotten boring? What was your inspiration?

I had a dinner once with a colleague of mine at USC and he said “You know, there needs to be a method book out there that has more original music.” He put that on my radar. He just got it in my head and got me thinking about it. Then a lot of time passed and I started thinking more about it. I mentioned it to Bob Margolis and he thought “Wow, think more about this – this is a great idea!” And then it was Bob’s publishing partner, Neil Ruddy, who hooked me up with Greg Rudgers and said this would be a perfect combination.

So Greg and I started talking, and the more we started talking the more excited I got about it. And we started looking at everything out there and we saw that “Ahh, there really is a need for this, and that, and look how all the books are starting with the flute crossing the break, and look at how the books are all starting with – wow – the horns starting so high in their register.” We thought “We could do better than this,” and we just thought there’s definitely a need.

So the first thing we did is go, “What are the notes we’re gonna start the instruments with if we’re gonna do this?” and we started talking and got excited about it and out of that excitement I went to work. Not only am I surprised that I’ve done it, I’m surprised at how much joy I’ve found doing this book. I’m certainly glad, having done it – in other words having finished it now is even the greatest joy, but even during the process I really enjoyed making this book and collaborating with Greg Rudgers on the creation of it.

So there are specific instrument things that you felt were missing or weren’t being handled as well as they possibly could be in other books. Making Music Matter does take an alternative approach to a couple things like flute range in the first few notes in an effort to improve the pedagogy from day one.

That’s absolutely right. All the books I looked at put all the instruments in unison, so they start them on a Bb major scale – (Sings) do-re-mi-fa-sol – the first 5 notes of the Bb major scale. Their goal is to get all the players on those 5 notes, and they’ll add la, they’ll add the first 6 notes.

But the problem with that is right away, think about the flutes. Bb, C, and then D – everything goes down. They cross the break right there between the C and the D-Eb-F. The horns are up there on concert Bb-C-D-Eb – they’re right up there with the trumpets. And that is too high for young horn players. The partials are too close together, the young players can’t find those notes, we can go on and on.

So we thought why don’t we start the flutes – to take them as an example – now it would have been really cool to start the flues on B-A-G, that’s just the left hand. But B natural, that’s a little too far away for a beginning band. B natural comes later. So we did a compromise, which ended up being even better. We did A-G-F for the flutes and the oboes so they get the left hand and then on F they bring in the first finger of their right hand. So they get to use both hands now but they aren’t crossing the break.

Saxophones are all on their written B-A-G that’s just left hand. The horns are down on their E-D-C, their low E-D-C of their C major scale, concert F major scale. They can find those notes down there. So all the instruments get to start on notes where they get some satisfaction. They’re not overwhelmed by having to overcome all these problems. So we have traded that for the fact that they don’t all play in unison now. You have to start out with chords right away in the book.

Yeah, I was going to say this is actually a good thing for the book overall because now you’re not worried about making them be unison on the first couple lessons. It goes hand in hand with these original Ticheli compositions that are interspersed throughout every lesson.

That’s absolutely right. But not only that, here’s the cool thing. If a band director wants to hear unison octave lines only, she can say, “Let me hear Group 1,” and you’ll see in the book there’s a set of instruments that are marked as “Group 1” instruments and every kid in the top left corner of his page it’s marked Group 1 Group 2 or Group 3. So the director says “Let me hear Group 1,” all the instruments in Group 1 play and it will all be unison.

Then she says “Let me hear Group 2” and it will be a set of instruments all in unison. And then finally Group 3, all in unison. So the director can still hear unison lines, unison octave lines by simply dividing into those 3 groups. What we did with this is allow the directors to have their cake and eat it too. They can have the unison lines if they want them, but not only that we also set up the first six lessons where kids get to learn their easiest, most natural notes on their individual instruments. It really is having your cake and eating it too.

It sounds like it! I’m already jealous I’m working at SmartMusic and can’t use it in the classroom.

(Laughs)

I have to get away from the book for just a second. You conduct honor groups and work with bands all over the country. Can you share an awesome conducting story from one of your clinics?

My goodness, you’re putting me on the spot with that one because there’s so many. There’s one that I’ll share – an embarrassing one. I conducted the Texas All-State Band, the very top Texas all-state band. And we were ending the concert with Blue Shades. We were all done, the concert was going really well and we got to the final piece, Blue Shades, and it was going so well. And I thought I just really want to enjoy the final piece with these kids, I want to have my eyes on the kids.

So I took my score off the stand. And I didn’t want to get off the podium and make a big deal of it, put it down on the floor. I took it off the stand and I just dropped it on the floor. Well that ended up – I’ve looked at it on video – that ended up looking more dramatic than I intended. It looked like I was saying “HA, we’re gonna do this without the score now.” And I dropped it and the whole audience went “WOOOAAHH” and they all started applauding really loudly as though I was making some big macho statement.

All I was trying to do is enjoy this moment with the kids and it turned into this macho “Ticheli doesn’t need the score to his own Blue Shades” moment. So that was a funny moment because it was an unintended show of machismo.

(Laughing) Perfect, that’s exactly the kind of story I was looking for.

So on that same concert we also performed Grainger’s setting of “Danny Boy” – “Irish Tune from County Derry.” So I used that moment to honor my teacher, Robert Floyd, who happens to be the executive director of the Texas Music Educator’s Association now. But he was my high school band director way back in the ‘70s. It was so cool for me to come back to Texas, conducting the top Texas high school honor band with my teacher on stage – he had to come out on stage and sit in a chair – and we performed that wonderful Grainger tune in his honor.

To me it was all the generations: my teacher watching me conduct my students (at the time) playing this piece in his honor. And so it was a really special moment and of course I broke down in tears while I was conducting that. And it was just a great memory for me.

That’s what it’s all about, really.

When you get down to it, that’s absolutely what it’s about. I just thought of another great story about that concert.

I’d love to hear more.

The end of that concert – Blue Shades – To me this is a great story about how we as music educators turn problems – how problems will lead us to solutions we’re often not smart enough to figure out on our own. Here was a problem: the solo in Blue Shades you know the big stand up clarinet solo in Blue Shades –

Yeah.

You know the principal clarinetist should play that. The second or third chair guy, he just played the heck out of it. I thought “Ahhh it would be great if he could be involved in some way.” So how do we handle that? Because the first chair guy was gooood, but the third chair guy was out of this world good! So we thought how could we handle it?

And then, I can’t remember which, one of the students said “Why don’t we both do it – we could trade off” because it’s in four phrases. And so we tried it. Not only did that solve the problem of allowing that third chair guy (who happened to be from my alma mater, Berkner High School) play part of the solo, but by having them both up there it added this energy that you never get with this solo because it became this conversation between two soloists going back and forth with each other, you know, sort of the battle between the two soloists, but it wasn’t a battle, it was friendly. And it was GREAT.

So it was a perfect example. Here we have a problem, and the problem led us to this solution I would have never found on my own.

Speaking of Frank Ticheli compositions, when students finish up with the first book there’s a second book. Do you recommend that mostly being for the second year then?

Yes, I mean it depends. This is the problem: some beginning band programs meet five times a week. Some meet only three days a week. Some meet only one day a week. So every individual music educator’s going to have to pace this according to their own needs.

For some, some of those programs that have beginning band five days a week, they might get to Book 2 before the end of their first year, sometime in the spring of their first year. On the average it’s probably a good book to start their second year with. Some programs it may take them well into their second year or their third year even. Because the second year is getting into Grade 2 – 16th notes and more sophisticated syncopations and slightly extended ranges. We didn’t extend the ranges too far. The trumpets get up to about an E, the low brasses up to about their D, the flutes are only up to their D. This is not major extension of ranges, but more tricky rhythms for sure! So it could even be used in the third year.

The reason I ask is once students then finish up the second book, it’s probably time for a more traditional set of pieces – moving on away from the method and into performance literature. What Frank Ticheli pieces do you recommend?

Ha – that’s a good question but you’re right. We designed it such by the time they finish Book 2 they are now ready for just about any Grade 2 piece and a lot of Grade 3 pieces in the actual repertoire. That was our point – to get them to that point. So any of my Grade 2 pieces by that point – Portrait of a Clown, this new piece I wrote called Peace, I have a piece called December Snow, I’ve got a piece called First Light – these are all Grade 2ish, Grade 1-2 area pieces. But by this point they’re even ready to take on something like Amazing Grace, some of my Grade 3 pieces by the time they finish Book 2. Maybe a few movements from Simple Gifts. Maybe not, but perhaps something like Shenandoah.

So speaking of Book 2 – those kinds of rhythms are the same things they’re going to encounter in these Grade 2 to 2.5 pieces. In other words, the method book has now progressed from setting them up where they get to learn some of this beauty of music and some really natural logistical and technical issues in book 1 into repertoire preparation.

That’s right. But we never drop the ball on that mission to teach beauty all the time, not just in the beginning. So even when you get to Book 2, you’re still doing tons of pieces that are just celebrating lyricism and beauty. I mean there’s a beautiful chaconne in there just called “The Lament” There’s a piece called “Desert Flower” that I think is very beautiful. All kinds of wonderful little pieces. And then there’s fun stuff like there’s a Cuban dance, there’s a little piece called “Catch Me If You Can” which is fun fast. There’s one called “Night in Nairobi” which is very fast.

But then there’s an easy version of my Shenandoah. In fact we end Book 2 not with a technical piece that’s really fast, but we end Book 2 with a simplified excerpt from my Shenandoah. Basically what I’m trying to do is end the book with “This is just as important as learning your technical skills” and we’re ending the book not with a technical piece but something that is all about beauty to remind them that this is just as important.

What kind of advice would you have for helping educators really make that point to students. As educators we know how important that stuff is – we’ve lived it, we’ve participated in all state bands, we’ve gone to school and taken music education classes. Band directors aren’t doing it for the money, obviously, so there’s an understanding among the educators, but passing that on to 13 year olds can be a real challenge. What advice do you have for educators who are really trying to drive that point home with their students?

Oh my goodness I could spend an hour on that. And also this is the topic of my lecture at the Midwest Clinic this winter. I’m giving a lecture there called “Beauty from the Beginning” but I’m also talking about this very question you just asked, which is “How do we remind ourselves of this value?”

There are a lot of thing we can do. It’s so easy to get bogged down in “I’ve got to teach this kid to put that pinky down on that key and now I’ve got to remind this kid over there that his tongue is getting in the way,” and it’s too hard and you forget to just step back a moment and say, “Wait a minute, why are we doing music in the first place?”

We have to remind ourselves, why did we get into music in the first place. I don’t know about you, but I got into it because it’s fun and because it’s beautiful. And we constantly have to remind ourselves that, and remind the kids of that.

So some concrete things we need to do are, when we’re up there on the podium, if we can just be the music more faithfully and not always be that band director up there who’s a technician. But be the music, it’s that simple. So if the music is slow and lyrical, we speak more slowly, we speak more lyrically, more calmly, so that we keep the kids in that world. If we’re doing a fast piece we can speak more quickly, we can be more abrupt with our motions, we can go back to that, but when the music is lyrical and beautiful, just be that.

All your gestures, when you cut off the band, even cut off the band slowly, don’t do a sudden jerky movement to cut off the band or tap the stand rudely. You cut off the band in the style of that music. You say to students, “You know what, can we bring that note out?” You don’t just say “Let’s bring out this note here,” you tell them why you’re bringing out this note. Is it a dissonance that they’re bringing out? Well what kind of dissonance is it? Is it a sad dissonance? Is it a poignant dissonance? Is it an angry dissonance? Is it a humorous dissonance? Dissonance can be humorous right? What kind of dissonance is it?

Now you’re involving the kids in this process rather than just saying “Do this,” “I’m gonna fix this,” and the energy goes one way. [You say] “Bring that note out” and they don’t know why they’re bringing the note out. But if you say why you’re bringing it out – I’m bringing the note out because it’s so sad and so beautiful. I want to bring out that sadness that’s in that dissonance. Now the students have an idea why he or she is bringing out that dissonance. Because it has to do with the beauty of that moment of music.

So that’s something that’s really important. I have to remind myself of this all the time when I’m on the podium. Is what I’m about to say to the student going to simply instruct the student, or is it going to inspire the student? So figure out a way that you’re not just instructing the student but also inspiring the student, that’s what we have to remember. That’s how I deal with it.

Frank thank you so much for your time. It’s been wonderful to talk with you, get your insights into teaching, the method book, how the method book’s built. You can find the method book – published through Manhattan Beach Music – it’s in SmartMusic so you can assign these lessons to your kids. Thank you so much for listening and thank you again to Frank Ticheli.

Thank you Ryan, it’s been my pleasure.

Before he became MakeMusic’s social media manager, Ryan Sargent earned a degree in trombone performance from Baylor University and begged many a middle school student to practice over the summer during his time teaching band.

Before he became MakeMusic’s social media manager, Ryan Sargent earned a degree in trombone performance from Baylor University and begged many a middle school student to practice over the summer during his time teaching band.

In addition to his role at MakeMusic, Ryan is an active jazz and funk trombone player in the Denver area and a member of the music faculty at the Metropolitan State University of Denver.