Musicians move to produce sound from their instruments. The quality of their movement determines the quality of their sound. By learning to move in accordance with the true anatomical design of the body, musicians can more easily produce their best sounds and prevent injury and limitation. Body mapping can help.

What is Body Mapping?

Body mapping is the method founded by William Conable and developed by Barbara Conable to consciously correct a faulty body map in order to rediscover healthy and easeful movement while making music.

Barbara wrote two books on body mapping: How to Learn the Alexander Technique and What Every Musician Needs to Know About the Body. She then created a course for musicians also called What Every Musician Needs to Know About the Body. Before she retired, she trained many of her musician students to present the course material to other musicians. Our organization of body mapping instructors is called Andover Educators.

The purpose of body mapping is to guide musicians through the process of remapping if they already hold erroneous beliefs about their body in movement and to prevent young musicians from ever losing the accuracy of their maps in the first place.

What is the Body Map?

The body map is the neuronal self-representation we hold of our body in our brain. It is literally a picture of our body located in the brain that corresponds to and governs, amongst other functions, our senses. We have numerous maps which represent ourselves in all of our various functions and behaviors.These maps interface and communicate with each other in complex ways.

When we are very small, our maps are normally accurate depictions of the actual anatomical design of the body, so young children move and play the violin or flute or piano with relative ease and comfort. However, these maps, which are changeable, can and frequently do deviate to become inaccurate representations of the body’s design.

Shoulder pain and tension and tendinitis in the forearm and wrist are two of the most common injuries that plague musicians. Here is how body mapping can help musicians prevent and overcome problems in these areas while simultaneously promoting freer arm movement for a bigger tone.

Preventing Shoulder Tension and Injury

Sometimes the map deviates from the truth because a child has modeled an adult in his life who has poor movement patterns. Sometimes the inaccuracy in the map stems from cultural myths. For example, if a child is told often enough to “get his shoulders down,” and he obeys by pulling muscularly down on the shoulders, he will eventually begin to feel that the shoulder region is structurally and functionally more part of the torso and is meant to sit on the ribs, instead of feeling the truth which is that it needs to function freely as a part of the arm. His neurons will begin firing differently to represent this altered notion of an arm and his arm movement will continue to deteriorate because his map is now dictating his movement in this new way. He will start to feel that the arm sprouts off the side of the body and he will lose free movement of his arms when playing his instrument.

The Mismapping

When students have pain, tension, and discomfort in the shoulder region, it is often because they have an inaccurate idea of what comprises a whole arm and do not have the arm socket mapped as being part of the shoulder blade.

The Whole Arm

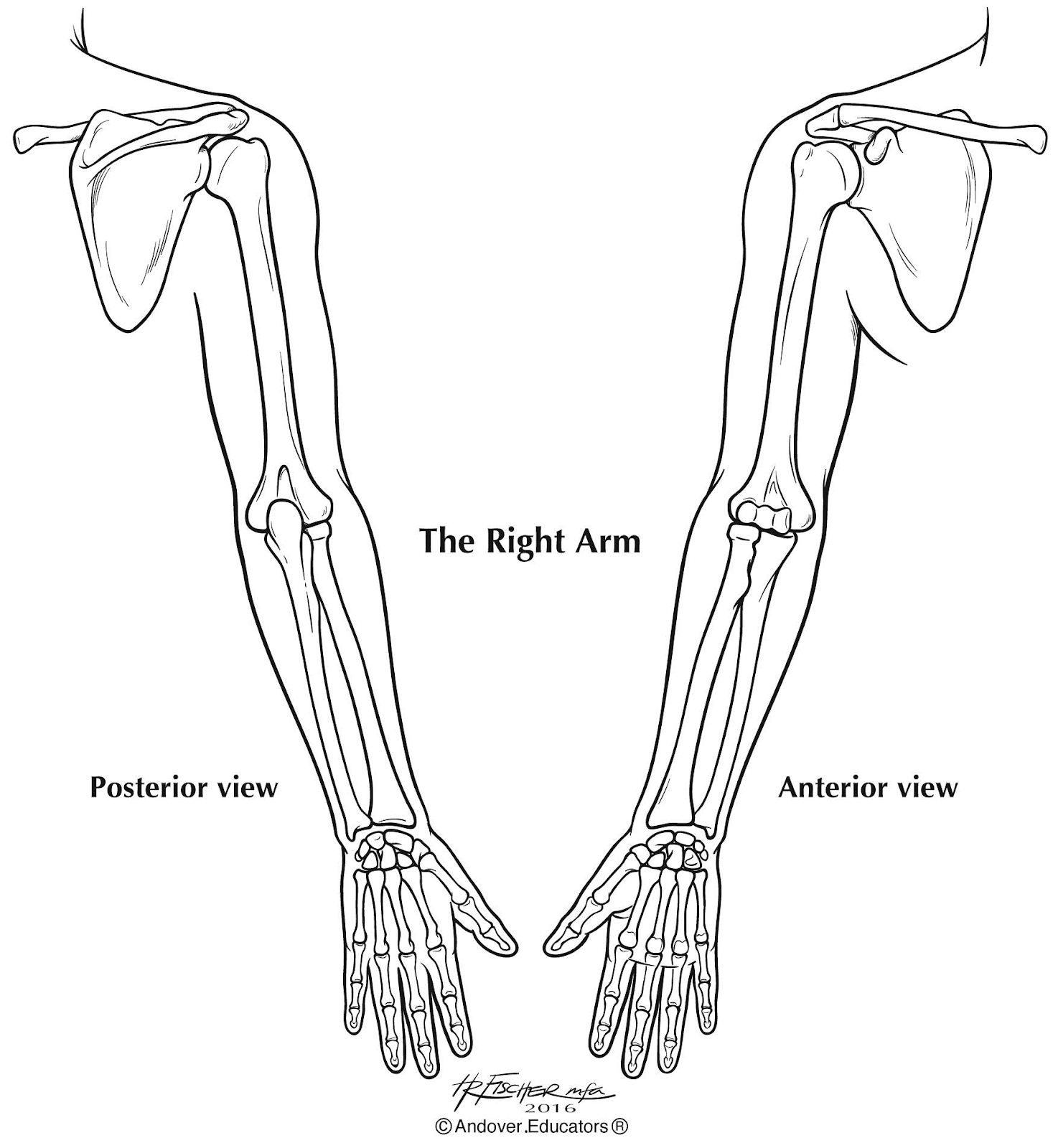

In listing the parts of the human arm, in its entirety, we need to include a collarbone and a shoulder blade, in addition to the upper arm bone (humerus), forearm, wrist, and hand. The socket for the “ball” of the humerus is actually built right into the side of the shoulder blade – in other words, the socket IS the shoulder blade. Because the shoulder blade is attached to the collarbone, there will always be movement from the collarbone’s joint with the sternum when we wish to move a shoulder blade.

If we do not allow the shoulder blade to move when we move our arms in front of us to play our instruments (perhaps because we were told early on to “keep shoulders down”) we create a strain between the ball and the socket. We set up a “tug-of-war” situation within our arm; part of it trying to go forward and part of it trying to stay back and down.

A human arm is not what we see on a Barbie doll. It is not a limb that sprouts off the side of the body. Because we have a collarbone and shoulder blade unit, we are able to do all the large arm movements that Barbie cannot do. Barbie can’t do the front crawl stroke because her makers did not equip her with a moveable collarbone and shoulder blade. Nor can Barbie play the violin, the piano, or the trombone for the same reason. When we play using our whole arm, we have both more arm mass and also more free arm velocity in order to create a more resonant tone from our instruments.

Movement Activity for Your Students to Explore the Whole Arm (Barbie Goes Swimming!)

Keep a Barbie doll in your studio or classroom to demonstrate how silly she looks when you swivel her arm around in a front crawl movement (or at least as closely as she can emulate that movement.)

Ask your students to explain why she looks so silly: “Why doesn’t this look right?” “What bones do we have that move for us when we swim that Barbie doesn’t have?” (Answer: She is missing a collarbone and shoulder blade.”)

Then have your students pretend that they are Barbie trying to swim. Ask them to place their right fingertips on the left collarbone and try to do the front crawl without allowing their collarbones to move. Then ask them to do the front crawl stroke the way they really would in the pool and notice how much more movement they feel their collarbone making under their fingers.

Allow them to experiment with their instruments to find a similar whole arm freedom. Ask them to discover how far and in what directions their collarbones need to move in order to play.

Preventing and Overcoming Tendinitis

One of the most common injuries that musicians suffer is tendinitis in the forearm or wrist.

The Mismapping

The most common cause of tendinitis in the elbow and wrist is the mismapping of the forearm’s rotation at the elbow joint. When the functions of the two forearm bones are not clear, often the wrong bone gets recruited to turn the forearm in rotation causing strain in the tendons.

Forearm Rotation

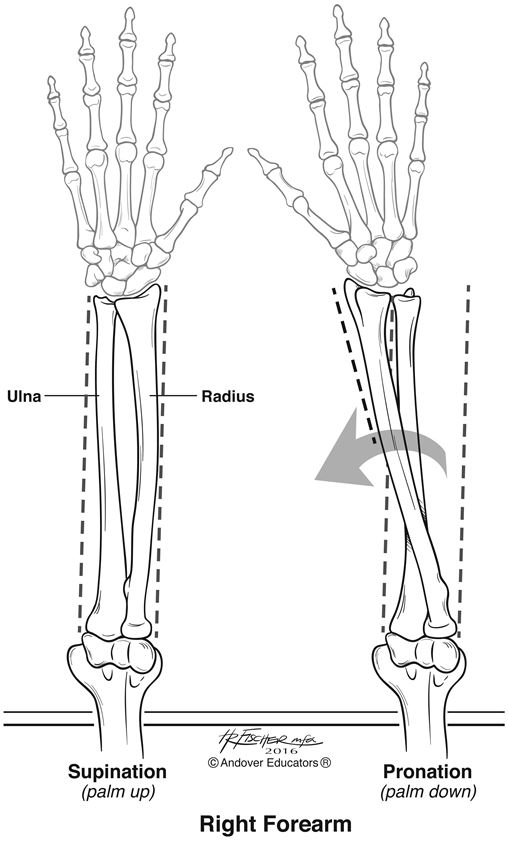

There are two forearm bones; the ulna and the radius. The ulna is on the pinkie side and the radius is on the thumb side. These two bones are parallel to one another when the hand is palm-up and when we turn the hand palm-down, it is the job of the radius (also called the “radial bone”) to “radiate” or rotate in order to cross over the stationary ulna. The radius is beautifully designed with a rounded swivel end where it meets the humerus (upper arm bone) to fulfill this function of rotating itself, carrying the wrist and hand bones along with it. The ulna is designed to bend the forearm at the elbow, not rotate it. However, musicians frequently try to turn the ulna – the wrong bone – in order to turn the hand from palm-up to palm-down. Because the hinge-like bending joint where the ulna meets the humerus cannot actually produce a rotation movement, the soft tissues in the forearm, specifically the tendons, attempt to accommodate and the result is they get stretched, strained, and inflamed in the process. This is called tendinitis.

Movement Activity for Finding Free Rotation at the Elbow Joint

To assess whether your student has this mismapping at the elbow joint, ask her to place her right forearm palm-up on a piece of paper on top of a table or desk. Then use a pen to draw a line on the paper along each side of her forearm. Next ask her to turn her hand palm-down, not allowing her humerus (upper arm) to aid in the movement. (We want to isolate the movement for the purposes of this exercise so that the rotating is not being aided at any other joints.) If her forearm stays roughly in between the two lines when the hand is moving to palm-down, or if the ulna slides at all across the paper, then you know your student has this mismapping.

In order to stay in between the two lines, the ulna would have to move off of its initial line and travel over the radius’ line, even though the ulna is not designed to perform this movement. The only way this can actually happen is if the tendons and other connective tissues are being strained. This is what it feels like when the radius is doing fifty percent of the rotation (instead of 100 percent) and the ulna is doing the other fifty percent of the rotation movement against its design.

Now encourage students who appear to have this mismapping to try the rotating movement again, this time while keeping the ulna stationary on its line and allowing only the radius to leave its initial line in order to turn palm-down. When turning the right hand palm-down like this, the radius will end up several inches to the left of the lines on the paper but the ulna will remain on its original line. (See image above.)

The movement will feel easier and freer than the first way and will allow for greater facility in the movement of the fingers because it removes jamming and restrictions in the hand and finger bones. This greater facility can improve intonation in string players and also increase the speed of playing when depressing keys or valves.

Body Mapping Outcomes

Since the Conables first began developing and teaching body mapping in the 1970’s, it has helped to save thousands of musicians’ careers who otherwise would have remained injured.

The hope of Andover Educators is that in future generations, body mapping will be a mainstream part of music pedagogy so that we are preventing injury in our students from ever happening in the first place.