The genetic wall between man and chimpanzee is that of tissue paper rather than reinforced concrete. In an analysis through measurement, the base building blocks between myself and a bark-eating bonobo is that of 1.2%. When faced with this, my focus is not drawn to the admittedly-shocking similarity, but rather the small 1.2%. What is within that small difference that makes me…me?

In a similar manner, I’ve moved this query into our world of music. What is the 1.2% that separates a routine concert from a performance that imprints itself into one’s life-memory? Why is playing with characteristic tone and methodical tuning simply not enough to satisfy our anthropic and musical needs?

I witnessed the Chicago Symphony perform Beethoven’s 7th on December 16, 2014. I was literally on the edge of my seat as I watched the hands of Manfred Honeck shape sounds into lush phrases. I was carried by each flowing sentence, entranced by the slippery chromaticism of the Allegretto, and ultimately enamored by the powerful conclusion of the Allegro con brio. What do I remember most fondly? For me, it was not the precision nor sensitivity, but rather the incredible phrasing of the performance.

At the time, phrasing was admittedly something I hadn’t committed much time to in my own teaching of middle school students. In addition to teaching characteristic tone and rhythmic literacy, my efforts also focused on topics like the importance not dropping one’s tuba on tile flooring. With time, patience, and trial and error, I not only integrated phrasing into my daily teachings, it took the forefront in many lessons and rehearsals.

Introducing Phrasing

I introduced phrasing to my beginning 6th graders with the following example.

“Let’s eat grandma!” ≠ “Let’s eat, grandma!”

The lesson: one small aspect completely changed the meaning of the message. I stressed the understanding that a series of notes played over and over again with different phrase shapes (or without phrase shape) must not be perceived as the same.

Further, we know young students love competition. With this, I would ask: “Does anyone think they can perform a two-measure phrase?” Students answered “Yes!”

Then I asked, “Does anyone think they can perform a four-bar phrase?” This resulted in the majority of beginners implementing an initial concept of phrasing into their first semester of playing. (This approach is initially kept at two measure phrases for flutes players and tuba players.)

When selecting literature for concert ensemble, I worked to find a balance between broad accessibility and pedagogical potential. What literature will capture the heart and mind of my youngest players, but also function as a pedagogical platform to ensemble awareness, style, and phrase shape?

When to Begin Bracketing

Once repertoire has been selected, consider the following before beginning the piece:

“When the technical problems of finger dexterity have been solved, it is too late to add musicality, phrasing and musical expression. That is why I never practice mechanically. If we work mechanically, we run the risk of changing the very nature of music.” – Daniel Barenboim

It’s common practice to take a small amount of class time for students to mark parts with their names, accidentals, and roadmaps…why not mark phrases? One non-obtrusive and clear method is for students to bracket the beginnings and endings. Here’s a look into how bracketing phrases creates a different perception of the music in front of them.

Example 1: Flute excerpt, “Pictures at an Exhibition,” Modest Mussorgsky

This example shows the beginning and ending of a planned phrase. In my experience, I have found that young students typically have the intuition to understand such a phrase even without the bracket.

Example 2: Flute excerpt, “Pictures at an Exhibition,” Modest Mussorgsky

Example 2 is less intuitive, per the rests between each measure. Here, the brackets remind the flautists that they’re part of a bigger phrase as they trade Concert D’s in a call-and-response manner with the brass family.

Further, the brackets (awareness of the phrase) instill a sense of listening responsibility within the students. Because they know that they’re part of a phrase, they must listen to other sections as they rest to continue the phrase in the correct direction.

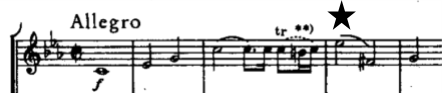

Example 3: “Serenade in C Minor, K. 388/384a”, W.A. Mozart

Example 3 shows the use of a symbol to indicate the strongest point of the phrase, with the understanding that the beginning of the bracket leads to that point, and dissipation begins immediately the strongest note, with the understanding that music “goes to” or “comes away.”

My focus is generally to develop the softer parts of the phrase, as controlling softer sound is typically more difficult. Feel free to create your own notational system for this! I have seen exclamation marks, highlighted notes, and smiley faces. My students gained a concerning amount of joy from drawing stars.

Beyond Bracketing

In addition to brackets, I “A” and “B” each student in a way that each person is surrounded by the opposite letter within the ensemble. With this, I assign breathing points to each letter to create a continuous ensemble sound through longer phrases that are difficult to make in one breath (remember the increased difficulty for flute and low brass players!).

Continue the implementation of bracket work and breathing assignments outside of the ensemble rehearsal. When meeting in sectionals, work to refine their understanding of not only the bookends of phrases, but also the refine the growth, peak, and decay of each phrase.

Rethink your warm up with this free ebook.

Rethink your warm up with this free ebook.

Modeling

Don’t underestimate the importance of modeling different approaches to phrasing on your instrument. In adding, you may consider singing phrases as well.

In my own progression as a musician and teacher, a most powerful lesson was not just to sing, but to sing with purposeful musicianship and intent. Practice singing away from rehearsal. While teaching, sing the phrase and conduct as you do so, further demonstrating what your ensemble should produce as they watch you. Create a sense of student accountability by having A’s play while B’s evaluate. Switch roles.

Key Points

- Phrasing is something that can (and should) be taught to beginning students

- Allow phrasing to be a consistent part of the learning process, rather than a “final step” that is added once the notes and rhythms are understood

- In your own study, make informed decisions on phrase lengths and shapes

- Take the time to share this information with your ensemble

- Take more time to ensure that your ensemble has correctly marked the information with your notation system of choice

- Sing or perform the phrase on your instrument

- Develop accountability and commitment to phrasing

- Self-Commitment to a phrase shape

- Accountability from players to perform the desired phrase

Putting phrasing at the forefront of your lessons and rehearsals can help to make that crucial small difference between an acceptable and an exceptional performance. I hope you find this post helpful as you develop phrasing with your students.