Sixth-grade band, orchestra, and choir directors face a complex challenge when starting their new ensembles each year. Sixth-grade students are diverse. Some come from strong music programs with adequate resources while others come from weaker music programs with fewer resources to offer students. In addition, students come from ethnically and socio-economically diverse elementary schools.

Additionally, while most students entering middle school have had five or six years of some form of elementary music instruction, the content differs from school to school. The 2014 National Music Standards state that all fifth graders should:

“Use standard and/or iconic notation and/or recording technology to document personal rhythmic, melodic, and two-chord harmonic musical ideas.”

However, how these skills are taught is not prescribed in these standards. The methods, approaches, and terminology used to teach these skills and understandings in elementary music programs vary widely, as there are many schools of thought regarding elementary music education (Kodály, Orff, Dalcroze, etc.)

One Challenge

Middle school music educators are faced with a dilemma. Do they assume that entering sixth-grade students have music skills and understandings or is it necessary to start at the beginning to ensure students can read music notation? They must then decide whether to formally or informally assess students’ prior knowledge and skills. These understandings and skills may not be easily evaluated by an ensemble director who uses different music labels. Teachers must then also determine whether or not to build on results of those assessments. The purpose of our study was to determine how elementary music educators and middle school music ensemble teachers assess music notation skills and understanding of their students. We sought to determine answers about vertical alignment and assessment of skills and knowledge of students exiting fifth grade and students entering sixth-grade ensembles.

Two fundamental research questions were developed:

- Do middle school music teachers assess and build on the skills developed in elementary schools, or do they start over when teaching notation?

- Do middle school ensemble directors and elementary music educators communicate with each other about their programs and about targeted skills they desire and teach?

Two Surveys to Rate Student Skills

To determine answers to these important questions, two similar surveys were developed: one for middle school ensemble directors, and one for elementary music educators. The two surveys were posted on national professional social media pages designed for music educators. The elementary survey was posted on a private social media page entitled “Elementary Music Teachers” and the middle school survey was posted on a private social media page entitled “Band Directors Group” which also attracts middle school choral and orchestral directors. Two follow-up reminders were posted on each page, to help ensure participation.

The surveys were comprised of questions requiring responses on a five-point Likert-type scale as well as open-ended questions. A total of 97 surveys from across the country were returned. Of these, 54 were completed by elementary music educators and 43 were completed by middle school band, choral, and orchestra educators. The qualitative and quantitative data were subsequently analyzed.

The Results

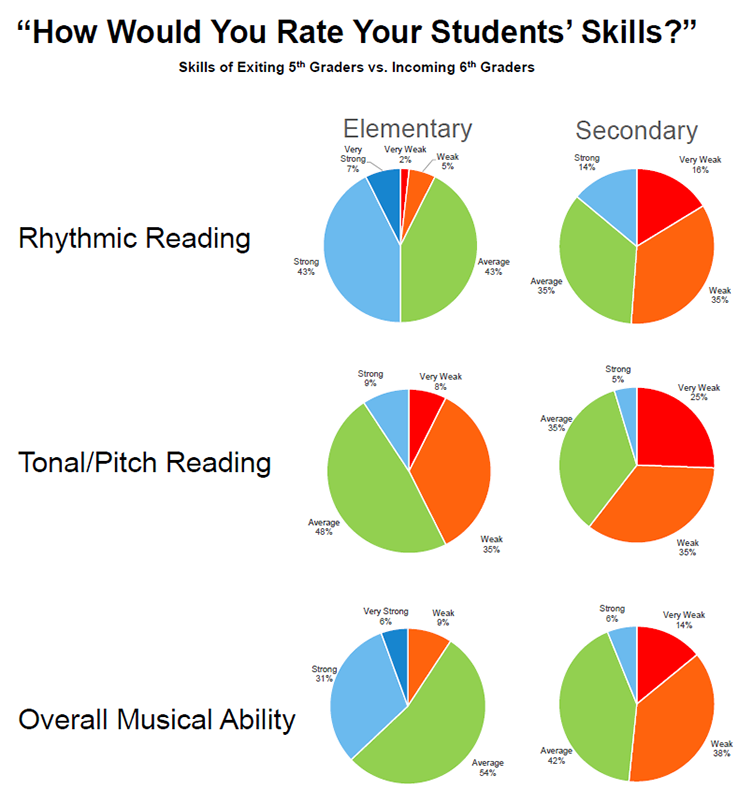

These charts show the participants’ results when asked to rate the musical skills of their students. The charts in the left-hand column are from the elementary surveyors and the charts in the right-hand column are from the secondary surveyors. The findings displayed above illustrate that elementary music educators rate skills of their fifth graders much higher than middle school rating educators rate the same skills of their entering sixth graders. This is worth discussing, as there is clearly a discrepancy between standards held by elementary and secondary music programs; a “better-than-average” effect, if you will.

Takeaways

From our surveys and data, we’ve acquired three big takeaways. Firstly, several elementary music teachers commented that they labeled notation with absolute pitch names and numerical rhythm counting, as opposed to using labels such as solfege and “ta, ta-ka-di-mi.” This practice could better prepare students for middle school ensembles, and is worth investigating. A method of assessment that gives entering sixth graders several ways to demonstrate knowledge and skills could give middle school educators valuable information. They could then build and extend on what was learned in elementary school without having to start from the beginning. Potentially, this could also keep more students engaged in music programs and could lower attrition in music ensembles.

Secondly, it is unknown whether students who possessed strong musical skills entering sixth grade were able to transfer these skills when placed in a new secondary ensemble that used a different language for describing notation. We found that little assessment of these new students’ skills by middle school ensemble directors was conducted. Such skills include transferring solfege labels of notes rather than absolute names of pitches (E, G, B, D, F), when reading music from graphic notation, or reading rhythm patterns using labels such as “ta, ta-di” rather than “1 te, 2 te.” If middle school teachers were to assess skills of entering sixth graders using either of the above systems learned in elementary school, they could learn more about these students’ understandings and skills and build upon those skills.

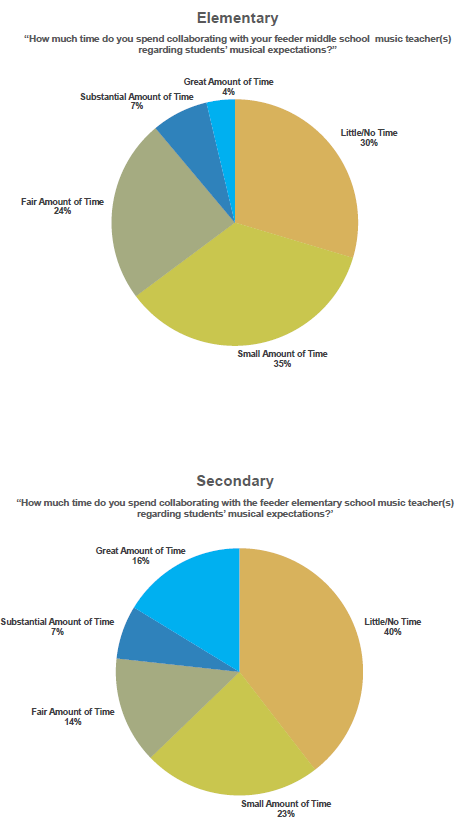

Lastly, but not of least importance, we found little collaboration between elementary and middle school music educators. As the graphs above show, a majority of the respondents, both elementary and secondary, did not report collaborating with teachers in other levels in their district to promote a smoother transfer of skills and knowledge for students moving from elementary and middle school. Insufficient time was expressed as a major reason for this lack of conferring. We speculate that more conversations could smooth the transition between elementary music and instrumental ensembles and keep more students engaged in music. This, in my opinion, is the most important of the three big findings. Without sufficient communication on both ends, no work towards bridging this gap can be done.

I strongly encourage music educators, particularly ones in close collaboration, to prioritize talking to each other, sharing goals and objectives, and working together more closely for stronger, more cohesive music programs and to keep more students engaged in making music.

This article covers recent findings from research conducted by Jonathan Martinez and Dr. Diane Persellin from Trinity University.